The First Black Woman to Own a Bank in America

Maggie Lena Walker:

The First Black Woman to Own a Bank in America

And Why Her Legacy Still Matters Today

Born Into Impossible Odds

Maggie Lena Walker was born in 1864, right at the tail end of the Civil War, to an enslaved woman and a Confederate soldier. She grew up in Richmond, Virginia, in poverty. Her mother worked as a washerwoman to survive.

Let that sit for a moment: a Black woman, born to an enslaved mother, in the Jim Crow South, would go on to become one of the most influential financial leaders in American history.

Rising Through Community

As a teenager, Maggie joined the Independent Order of St. Luke, a mutual aid society founded in the 1850s by a Black woman to care for women and children. These kinds of organizations were lifelines for Black communities—providing insurance, burial funds, and financial support when no one else would.

Maggie didn't just participate. She led. She worked her way up to become the Grand Secretary-Treasurer of the organization, at a time when it was nearly bankrupt.

Instead of letting it collapse, she transformed it.

"Take the Nickels and Turn Them Into Dollars"

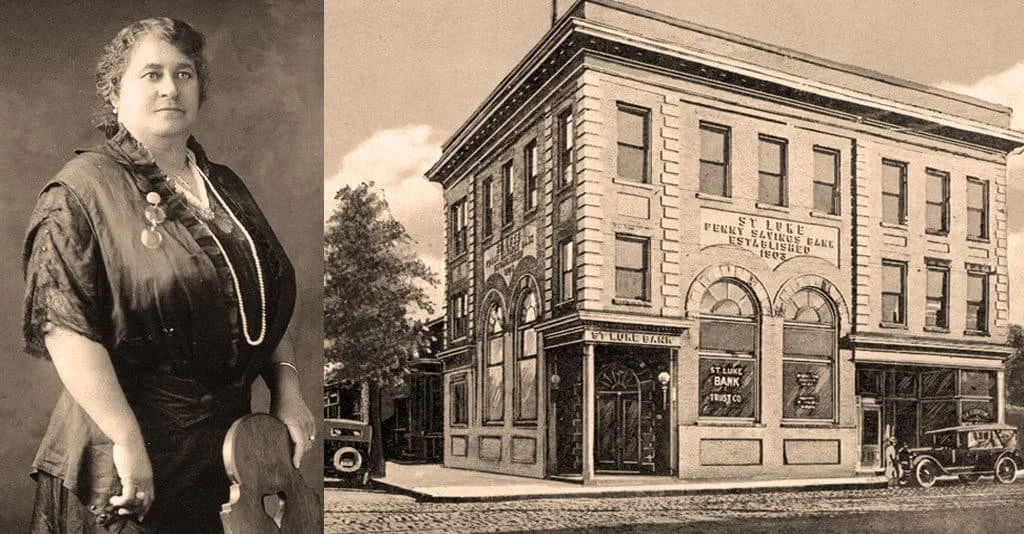

In 1903, Maggie Lena Walker founded the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank in Richmond, Virginia, becoming the first Black woman in America to charter and preside over a bank.

But before the bank, she built the foundation. She established a small community insurance company for women through the Independent Order of St. Luke, creating a safety net where none existed.

Then came the bank, making both fiscal and gender history.

Think about what that means.

At a time when women (especially Black women) couldn't even open bank accounts without a husband's permission in many places, Maggie Walker was running the bank.

Her bank was:

Organized by Black women

Financed by Black women

Led by a Black woman

This was unprecedented.

The bank became a powerful tool for Black self-help in the Jim Crow South. It didn't just serve Richmond's adults. It taught the importance of saving to Black children by giving out small banks that encouraged them to save their pennies.

As Walker said in her address to the St. Luke Annual Convention in 1901:

"Let us have a bank that will take nickels and turn them into dollars."

By 1924, the bank had grown to more than 50,000 members.

And while the Great Depression saw the collapse of many of America's banks, St. Luke's survived. Why? Because it was built on a foundation of community trust and mutual support, not speculation or greed.

It eventually merged with two larger banks to form Consolidated Bank and Trust Company, the oldest continuously existing Black-owned and Black-run bank in the country.

It continues to operate today in Richmond as Premier Bank: Consolidated Division.

Over 120 years of service. One woman's vision. Still standing.

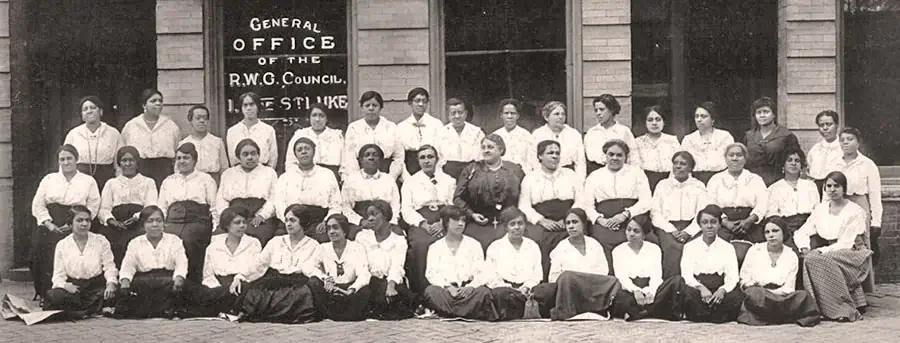

A group photo of Maggie Lena Walker’s office staff in 1917.

Banking Reimagined: For the People

Maggie didn't just open a bank, she reinvented what banking could look like for her community.

Extended hours. She kept the bank open on weekends so working people could actually access their money.

Micro-loans. She made loans as small as $5, because she understood that sometimes a small amount of capital could change someone's entire trajectory.

Centering women. Here's the part that still blows my mind: she required that wives co-sign their husbands' loans. At a time when men controlled nearly all financial decisions, Maggie Walker flipped the script—acknowledging that Black women were central to the economic lives of their families and communities.

Her philosophy was simple and powerful:

"Take the nickels and turn them into dollars."

Beyond the Bank

Maggie Lena Walker wasn't just a banker. She was a movement builder.

She served as Vice President of the Richmond chapter of the NAACP. She held leadership positions in the National Association for Negro Women. She was a member of the National Negro Business League—the organization that connected Black entrepreneurs across the country.

And she opened a department store that exclusively featured brown-skinned mannequins—because representation mattered to her, even in retail. She believed in uplifting Black women through every avenue possible.

Maggie Walker and the Juvenile Branch of the Independent Order of Saint Luke, source: encyclopediavirginia.org

A Black-Owned Bank That Survived the Great Depression

Here's what might be the most remarkable part of her legacy:

Her bank survived the Great Depression.

When banks across America were collapsing—when people lost everything—the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank stayed open. Why? Because it was built on a foundation of community trust and mutual support, not speculation or greed.

The bank continued operating until 2009 (it later merged with another institution), making it the longest-running Black-owned bank in American history.

Over 100 years of service. One woman's vision.

Why This Story Matters Now

We're in a moment where Black economic empowerment is being discussed more than ever. The question Maggie Lena Walker answered over 120 years ago is still relevant today:

What would it look like if our financial institutions were rooted in community?

What if banks existed to serve the people… not the other way around?

Maggie Walker showed us it's possible. She didn't wait for permission. She didn't accept the limitations placed on her. She built something that lasted generations.

The Connection to Black Scranton Project

As the founder and CEO—and honestly, the primary caretaker—of the Black Scranton Project Center for Arts & Culture, I spend a lot of time inside a former bank.

I unlock the doors.

I check the heat.

I greet the community.

I worry about repairs, programming, safety, and sustainability.

And sometimes, standing in the middle of this historic space, I catch myself thinking:

“You kinda own a bank.”

Or more accurately—Black Scranton owns a bank.

Not in the traditional sense.

But in the way that matters.

Being responsible for a bank building (especially as a Black woman) has made me think deeply about legacy, access, and the history of who has been trusted to hold space, resources, and power.

That reflection led me to someone whose story deserves to be spoken out loud, especially during Black History Month.

At the Black Scranton Project Center for Arts & Culture, we operate out of a historic bank building built in 1926—the same year Dr. Carter G. Woodson established Negro History Week (now Black History Month).

That's not a coincidence we take lightly.

This Black History Month, as we celebrate 100 years of Black History Month and honor the legacy of those who came before us, we're proud to spotlight Maggie Lena Walker—a woman who turned nickels into dollars, and limitations into legacy.

Learn more:

Written by Glynis M. Johns | Black History Month 2026