Frederick Douglass Was Here

What His Visits Reveal About Scranton, Freedom, and Black Life in NEPA

Set the Stakes (Not the Scene)

Frederick Douglass did not travel casually. When he came to a city, it was because ideas, people, and movements were already in motion.

Scranton was one of those places.

Douglass visited Scranton multiple times between the 1860s and 1870s, speaking to packed audiences in a rapidly growing industrial city—one shaped by coal, railroads, immigration, and a small but significant Black population finding its footing in the aftermath of slavery and the Civil War.

This post uses newspaper clippings, advertisements, and community memory to ask a bigger question: What does Douglass's presence tell us about Scranton—and Scranton's place in Black freedom history?

Scranton at the Time Douglass Arrived: 1860s

In the decades following the Civil War, Scranton was booming.

Population in the late 1860s: roughly 35,000–40,000 people

The city was dominated by coal, rail, and industrial labor

Immigrant communities were growing rapidly

The Black population was small in number, but deeply rooted, made up of:

formerly enslaved people

free-born Black Northerners

Civil War veterans

families who arrived via informal and formal freedom networks

In cities like Scranton, being Black often meant being hyper-visible and politically vulnerable, even as Black residents built churches, families, and institutions.

Douglass arrived speaking directly into that reality.

"Frederick Douglass, One of the Most Noted American Public Speakers"

The newspaper advertisements and coverage matter because they tell us how Douglass was framed—and how the public was expected to see him.

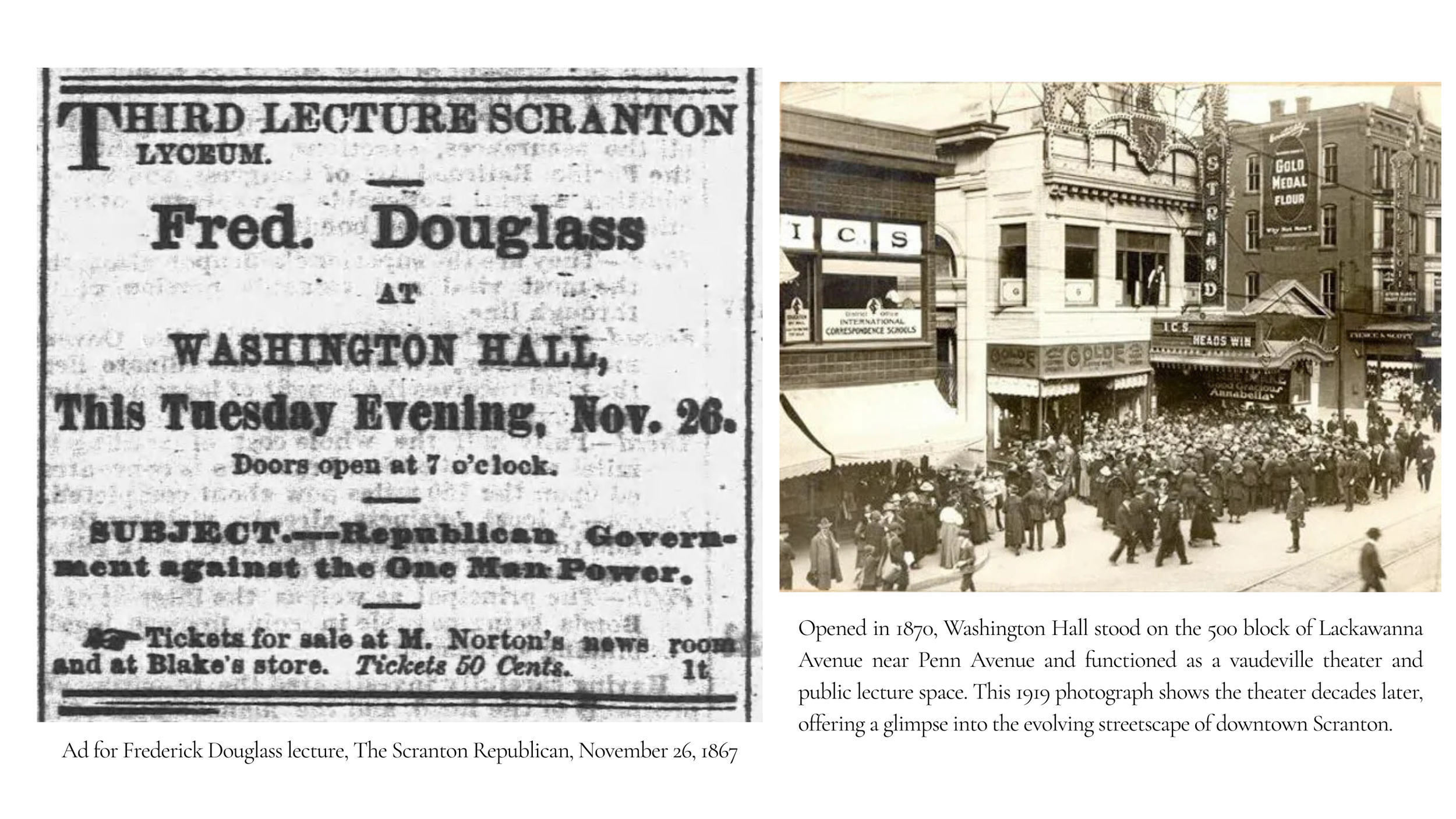

One advertisement announces his lecture plainly.

Another editorial sharply criticizes the lecture committee for promoting him as a "Negro orator."

The Scranton Republican, November 25, 1867

"…the being announced as a curiosity or an anomaly must be extremely unpleasant if not positively insulting."

The paper insists Douglass should be heard:

"…not because he is a Negro, but because he is a man—a man of intellect, eloquence, and acquirements."

This language reveals the tension of the era:

Douglass was admired

His brilliance was undeniable

But racism still shaped how institutions spoke about him

That contradiction is the story.

And yet, despite the "unpopular price" of tickets, the lecture was a success. The Scranton Republican reported that "Washington hall was suffocatingly filled" to hear Douglass speak on "Self-Made Men."

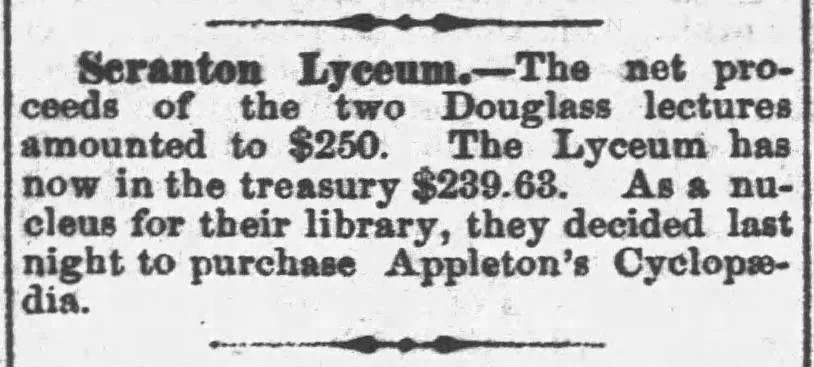

Net proceeds of the Douglass lectures, The Scranton Republican, November 30, 1867

The two Douglass lectures brought in $250 in net proceeds — used to purchase Appleton's Cyclopædia as the foundation of a new library.

Why Douglass's Message Landed Here

When Douglass lectured in Scranton—on topics like "Self-Made Men" and republican government—he wasn't offering inspiration alone. He was dismantling myths.

He challenged:

the idea that success comes without structural advantage

the belief that race determines intellect

the lie that freedom ended with emancipation

In his own words:

"He himself, when a slave, prayed three years for freedom. He did not pray as loud as some, perhaps, but he found that the Lord did not answer his prayers until he prayed with his legs. He then felt the answer coming right down."

This wasn't abstract philosophy. This was testimony.

Douglass also used his lectures to lift up other Black thinkers. He spoke of Benjamin Banneker, the Black astronomer from Maryland, who taught himself mathematics and surveying — and who sent Thomas Jefferson an almanac with his own astronomical calculations after Jefferson claimed mathematics were "impossible" for Black people.

"Banneker was not one of these mulatto lecturers, who it is said get all their brains from the Anglo-Saxon line of their ancestry, but a pure African."

Douglass wasn't just inspiring. He was dismantling myths with receipts.

For Black Scrantonians—many of whom had escaped slavery or were one generation removed from it—these weren't abstractions. They were lived truths.

Douglass's words validated Black dignity in a city where Black life was often undocumented, minimized, or erased.

Scranton, NEPA, and the Underground Railroad

Scranton and the surrounding region did not exist outside the freedom struggle.

Through sustained work by community historians like E.J. Murphy, we know that:

Northeastern Pennsylvania functioned as part of freedom networks

The region served as a waypoint and, for many, a final destination

Black residents here included people who had fled Southern plantations, escaped via informal routes, or settled intentionally after gaining freedom

Thanks to EJ Murphy's leadership, Waverly and Scranton are now recognized as part of the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom, in partnership with the Waverly Community House and the National Park Service.

This recognition affirms what Black communities have long known: NEPA was not on the sidelines. It was part of the movement.

Why This History Matters Now

Douglass didn't just pass through Scranton. He spoke into a city shaped by migration, labor, race, and possibility.

His visits remind us that:

Black history in NEPA is not accidental

Black residents here were not merely workers, but thinkers, veterans, organizers, and survivors

Freedom didn't end with escape—it continued with choosing to stay

This is why Douglass Day matters.

From Archive to Action

This Black History Month, we honor Frederick Douglass not just by remembering him—but by locating him.

In Scranton. In NEPA. In the ongoing story of Black freedom.

Celebrate Douglass Day With Us

Douglass Day Trivia Night 🗓 Thursday, February 13 | 6 PM 📍 BSPCAC | 1902 N. Main Ave

Categories include Black culture, American history, PA & local history, pop culture, and entertainment.

Free. Fun. A whole vibe.

🔗 RSVP: blackscranton.org/bhm2026